THE LONG SHADOW OF FASCISM ON TWENTIETH CENTURY MUSIC

Though the Anglosphere knows Napoleon Bonaparte as a warmongering tyrant of short stature, there was a time he was heralded as the torchbearer of liberal policy and a new Romantic thought: egalitarianism for all (well, all white men, to the further oppression of women and minorities). Ludwig van Beethoven saw in Napoleon a hero, telling his publishers that the subtitle of his new symphony was to be Bonaparte. But when informed of the news that Napoleon had crowned himself emperor, Beethoven supposedly flew into a rage and violently scratched out the dedication. When published, the symphony bore the title: Sinfonia Eroica… ‘composed to celebrate the memory of a great man’.

The history of the European continent is easily sketched in the tyrants that worked in blood to reshape its borders to their own ambitions – and even those not considered tyrants wrecked destructive tyranny through their colonial ambitions around the globe. The third program of ANAM’s Brave New Worlds series takes a very small slice of the Western music affected by this tyranny, examining how inextricably linked each piece is with its contexts and history.

No need to stand for the opening hymn, a work that has run the gamut of representing liberal Romantic thought and oppressive nationalistic totalitarianism. Joseph Haydn’s Kaiserhymne was written as a birthday gift to Austria’s Emperor Francis II in 1797, setting the poem Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser (“God save Francis the Emperor”). Both saw in it a Germanic equivalent to the stirring God Save the King and the newly written La Marseillaise, the anthems of Austria’s biggest challengers in the ongoing continental struggle for power.

The Kaiserhymne was adopted as the Empire’s anthem in 1806. New revolutionary words by August Heinrich Hoffman von Fallersleben made the Kaiserhymne emblematic of the German nationalist movement, seeking for the union of the Germanic monarchies into one liberal nation-state. But all too easily the rallying “Deutschland über alles” (“Germany above all”), initially meaning that the national project and identity was greater than any individual monarchy or autocrat, was poisoned by the rapid ascension of the Nazi party to power through the 1930’s. Singing this first verse immediately followed by the Horst-Wessel-Lied, the song of the Nazi Party, the anthem became undeniably linked to Adolf Hitler’s regime.

When the Nazis were defeated in 1945, the newly established West German government were faced not only with rebuilding a nation but a culture, where the identity of ‘German’ had forcibly been assimilated into that of ‘Nazi’. The process of denazification sought not only to deprogram and come to terms with the preceding decade, but to untangle whole corners of language and identity now holding sharp double meanings or symbolism.

The question of what to do with this poisoned anthem was long discussed – progressives wanted this to be a moment where a new idealistic Germany, untethered to the crimes of the past, could be symbolised by a new anthem, but traditionalists argued that despite the recent history, the anthem still stood for the German democratic nationalism of 1848, ideals lost and tarnished in the 1930’s. Over seven years of debate, traditionalist sentiment won out and the third verse of Hoffman’s text (Einigkeit und recht und freiheit…; “Unity and justice and freedom…”) was chosen. Infrequent conservative pushes to reinstate the first verse have not been successful, and its live performance is taboo to most Germans to this day. In 1990’s reunification of East and West Germany, the third stanza was again affirmed as the national anthem.

The story takes a different turn in East Germany, where a new anthem was selected. Firmly setting aside the past was much easier for the communist regime, in the fist of Joseph Stalin’s control, seeking to define a new identity altogether. The anthem Auferstanden aus Ruinen (“Risen from Ruins”) was composed by Hanns Eisler on text by Johannes Becher. Calling for German reunification (under the East German socialist system), the lyrics were abandoned in 1973 as the East continued to cast the West as the enemy, fortifying its borders to prevent its citizens defecting, and the anthem was performed as an instrumental. As reunification became increasingly likely with democratic elections, diplomatic thaw and opening of borders across the Iron Curtain, the lyrics were unofficially reinstated and became a rousing symbol of national unity for Germans in the East.

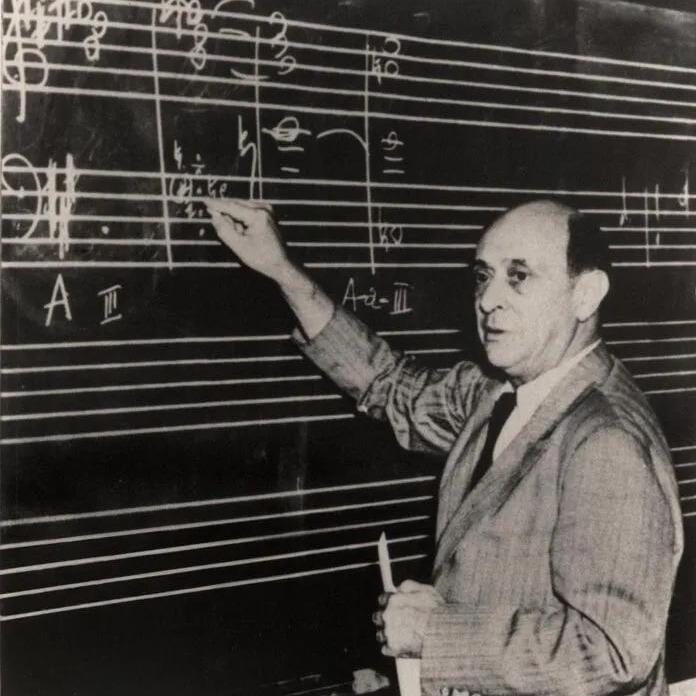

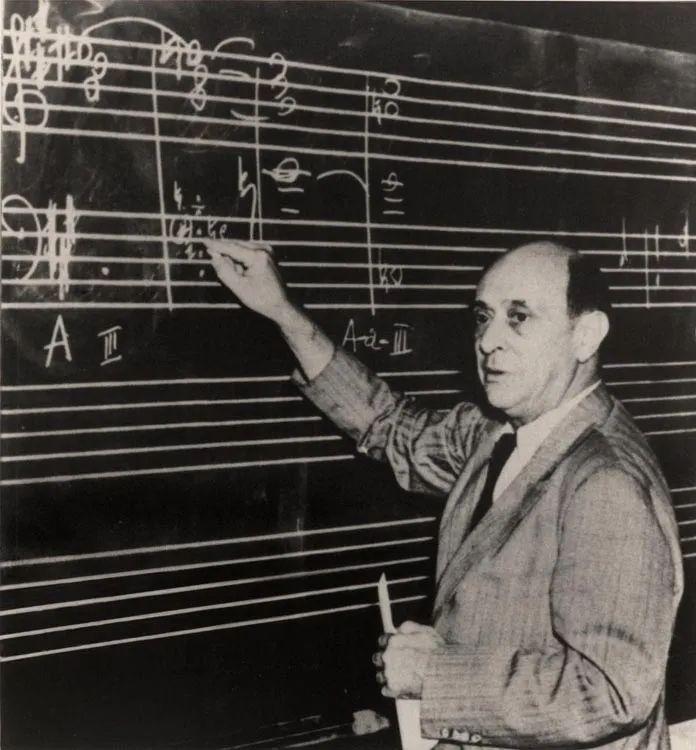

Growing up in Vienna, composer Hanns Eisler was a student of Arnold Schoenberg, but the two fell out over Eisler’s uncompromising Marxist beliefs. Moving to Berlin in the mid-1920’s, his early serialism influenced a lifelong output of anti-fascist and political songs, especially working with playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht. His musical output and membership of the German Communist Party made his music an immediate target when the Nazis swept to power in 1933, and Eisler soon fled the country, taking a post at the University of Southern California in 1942. His musical output continued to be politically motivated, strongly anti-fascist and now reflecting on his exile, notably captured in his Hollywood Liederbuch, but his leftist views saw him victimised by the American government shortly after the war ended. Eisler was interrogated by the House Un-American Activities Committee, who fervently went after Americans and foreign nationals alike and fuelled the Red Scare of anti-communist sentiment, and he was deported in 1948 despite activism of artists across the world including Pablo Picasso, Charlie Chaplin, Igor Stravinsky and Aaron Copland.

It was with dismay rather than bitterness that Eisler accepted his new exile – having faced and fought against fascism through his music and beliefs his whole life, he described it as “heartbreaking” to be deported, once again the victim of fascistic tendencies of a nation which promised to be just the opposite. And settling behind the Iron Curtain in East Germany, Eisler was again faced with the indefatigable spectre of fascism as Stalin’s grip on the Eastern bloc saw the working class Eisler championed further impoverished and their dissent violently contained. His musical output, including theatrical and film music, songs and a small amount of chamber music, was largely ignored outside of East Germany and has only recently been gaining wider recognition, both as a product of its time for Eisler’s intellect and politics, and for its timeless humanism and anti-fascist sentiment.

Hanns Eisler’s teacher Arnold Schoenberg shared his student’s experience of exile, also leaving Berlin for the United States as the Nazis seized power. This flight was not a novel experience for the groundbreaking father of serialism in Western music – as an uncompromising devotee to the emancipation of dissonance and as a working-class Jewish man, Schoenberg was never accepted in his native Vienna. Attempts to have his music performed were so often faced with vitriol from conservative Viennese audiences that he established his own music society, which privately performed works by himself and his protégés in concerts exclusively for its vetted members. The outsider nevertheless sparked the imaginations and talents of a generation of composers, including Eisler, Alban Berg and Anton Webern.

Though his works received mixed reception across his life, Schoenberg’s mastery of compositional skills and theory saw him take on teaching positions at conservatories. Invited to the Akademie der Künste in Berlin in 1925, Schoenberg saw the rise of the Nazis first-hand, and though used to antisemitic vilification from his time in Vienna, his professional and personal life were increasingly affected: the hostility towards his works was in part influenced by antisemitism, and there are accounts of him being refused service and at least once being removed from a hotel when on holiday due to a ‘no Jews’ policy. When the 1933 law prohibiting Jewish people from holding university positions was passed by the Nazi controlled Reichstag, Schoenberg fled to the United States.

A tyrant going to war over nationalistic ideas, seeking once and for all to control the European continent – to Schoenberg, this was Hitler, but to many in the early nineteenth century, this was Napoleon. Like Beethoven, Lord Byron had idolised Napoleon’s ascension as anti-monarchist, republican and more liberal policies, including education, tax and justice reforms, overseeing significant economic growth that placated the general public in the face of his consolidation of power, restriction of press freedom and ruthless exiling of any political rivals. His brutal colonial policies and reestablishment of slavery in French-controlled colonies was also conveniently overlooked by those idolising him.

At the time of Napoleon’s rise, both France and the continent were wracked by instability in the aftermath of the French Revolution: inside France, food shortages and political warring saw the revolutionary spirit morph into an ugly machine of retribution with thousands sent to the guillotine and rapid changes of government and constitutions; and across Europe, the established monarchies saw a weakened France ripe for their own taking, reinstating the House of Bourbon and through it their influence over the nation. Napoleon played factional games inside of France and followed his instincts to the winners’ sides, using his own military victories to gain public acclaim and quickly rising to the rank of general. A French victory over Austria in Italy in 1797 sealed Napoleon’s fame, and even a naval defeat by the British when returning from Egypt in 1798 couldn’t sully his reputation. Upon his return to Paris, he led a coup against the existing government, being granted total control through the newly created position of Consul in 1799.

A further series of military victories by France saw a brief period of peace established: Austria was again defeated in Italy when Napoleon led a reserve force across the Alps in 1800, and Britain soon after signed a peace treaty with France. Peace on the continent only boosted Napoleon’s popularity, and as he followed through on promises to restore the French economy and reform systems, a plebiscite named him Consul for life – Emperor in all but title. As political enemies inside and out of France plotted bolder attempts to remove him from power, Napoleon took the advice of his allies to claim the title of emperor. Ascendant to total power in France and then coronating himself King of Italy, Austria saw France’s claims on Italy as a provocation, and peace was shattered. What Austria envisioned as an offensive campaign quickly turned to desperate defence in the face of overwhelming French military ingenue, and by 1812, France ruled continental Europe from the Portuguese border of Spain up to the doorsteps of Russia and the Ottoman Empire.

It wasn’t Napoleon’s turn to conqueror that turned Lord Byron’s sentiments against the Emperor – it was his folly of not accepting defeat. A rapid series of defeats in 1813 saw France’s position weakened, and this was exacerbated by Napoleon’s inability to accept a peace treaty with favourable terms for France. The French Senate had to depose Napoleon, and he was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba. It was this refusal to capitulate, a refusal to look defeat in the eye, that made Byron finally question his admiration. At the time of Napoleon’s rise, his popularity was buoyed outside of France for the egalitarian principles he came to represent: a hero who ‘came from nothing’, representing the potential of every man. That this was based on fallacy and myth did not bother Byron (Napoleon himself came from nobility, if only minor), and a cult of admirers imagined a Europe united under post-Revolution France’s liberal (for the time) ideals.

So to see their hero so resoundingly defeated by the monarchic establishment was a blow to Byron and these ideals. Not even the dramatic Hundred Days, in which Napoleon escaped from exile, rallied the nation, and struck out for one final campaign before his defeat at Waterloo, could redeem him. In fact, the hubris to bring France further into defeat as the result of his actions only deepened the sense of betrayal to all the values Byron had thought Napoleon stood for.

The Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte was penned following Napoleon’s first abdication in 1814, and takes a similar strain to Beethoven’s own celebration of the “memory of a great man”. Though Napoleon lived after his humiliation, Byron lamented that it would have been better if Napoleon had “fallen on his sword.” In wonderful notes provided for this concert, available in the concert program, Phil Lambert deconstructs the poem and its use of mythological heroes and their own tragedies as representations of Napoleon’s own folly. Most notable is the comparison Byron makes of Napoleon to Prometheus, the Greek god who stole fire from the Olympians to give to humanity and is both punished for his transgressions and does not see the dangers that fire also represented. Prometheus thus represents a core human characteristic of striving for advancement and progress, and the unintended consequences of ambition. In this casting, Byron betrays his lingering admiration of all Napoleon stood for, to him a Promethean figure who brought with him the promise of enlightenment and progress, who strove too far and was only brought down by his own human nature.

This sense of questioning and admiration running through Byron’s text takes an ironic tone in Schoenberg’s setting of the text, penned in 1942 in the aftermath of Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbour. Schoenberg had no lingering positivity for Adolf Hitler, the man who had forced Schoenberg out of Germany and spewed hatred towards every part constituting the composer’s identity. Published before the true atrocities of the Nazi regime were truly known, Schoenberg’s Ode contributes to a collection of works that seek to satirise and mock the Nazis and their fervour, turning them into objects of ridicule instead of fearsome enemies. In his introductory note to the text, Schoenberg compares the Nazis to bees, and Hitler as the queen by extension, both a tongue-in-cheek demeaning of the leader and a more earnest questioning in the comparison to the waste of soldiers (“resemblance of the valueless individual being’s life in respect to the totality of… its representative”).

The work has a surprising sense of tonality being from the composer who emancipated dissonance – but a closer look reveals that a serialist toolkit underpins this work. A tone row (a specific arrangement of the 12 chromatic notes of an octave) forms the chord structure (A, C, F, G-sharp, C-sharp, E, B, D, G, B-flat, E-flat, F-sharp, where the final six notes are the first six transposed a step higher). A moment where Beethoven’s fifth symphony and La Marseillaise are simultaneously quoted, woven into each other, as the reciter proclaims “the earthquake voice of victory” – where La Marseillaise would have signalled Napoleonic triumph to Byron, in Schoenberg’s hands this becomes a victory of the oppressed French, rising up against the bluster of the Germans, further reinforced by Beethoven’s famous “fate” motif.

The use of a reciter is also notable: rather than the perceived refinement of a sung-through vocal line, the more quotidian spoken line gives the speaker a sense of detachment from the piano quintet. Schoenberg had been experimenting with variations of vocal delivery between spoken and sung, most notably in Pierrot Lunaire, which went on to be the name for this unique ensemble. Whilst Pierrot calls for a spoken quality at specified pitches, the Ode gives a contour and rhythm without specified pitch – the reciter must instead use the contour given to inform their inflection. That English is a second language to Schoenberg is at times apparent in the rhythm of the set text, but again, intentionally or otherwise, the character that these unpredictable rhythmic stresses provide add to the sarcasm and derision of this fallen so-called hero.

The final segment of the text turns to Byron’s new hero: George Wellington. For Schoenberg, this is an easy metaphor to update, with Wellington still representative of the ideals of American exceptionalism, seeing the US as instrumental in securing an Allied victory in Europe. And as the Ode received a national broadcast on 25 November 1942, it became one of the many rallying cries for victory, far across the Atlantic.

As swiftly as the Germans had initially seized Europe in their grip of terror, the Allied forces had turned the tide in 1945 and marched through Germany towards Berlin. Though the existence of the concentration camps across Germany and Poland was common knowledge thanks to testimonies of escapees and the ingenuity of those inside constructing radios and arranging accounts to be smuggled out, nothing could have prepared the Allied soldiers for the scope of the horrors they would encounter. Dwight D. Eisenhower alarmingly prophesised the potential for future denialism of what would come to be called the Holocaust, and so the commander of the Allied forces and future US president ordered troops to extensively document the camps or their remains, destroyed by fleeing SS officers seeking to cover up their crimes against humanity.

The ruin that Germany found itself in after its surrender in May 1945 was not just physical. The Western and Soviet forces who occupied the country in the immediate aftermath wrestled with the task of deprogramming an entire country and ensure Nazism could never rise again, whilst also seeking justice for the genocides and war crimes, and retribution for Germany’s acts of war. This denazification became less important to the West as the Cold War’s tensions steadily increased, and the sheer administrative burden of processing millions of ex-Nazi Party members could not be surmounted. A palpable tension ran through this society, who personally faced consequences through supply chain crises, overwhelming suspicion and unmeasured punitive action (to not have been a Nazi Party member was taboo during Hitler’s reign – fierce opponents were forced to be members for their safety or conscripted to the armed forces; and then faced sanctions on their employment or forced labour by the Allies as a result of their past records), and yet saw higher-ranking Nazis avoiding consequences, regaining positions in the new German administration or being fought over for their expertise by foreign powers (see Nazi scientists employed by NASA in Operation Paperclip).

The 17-year-old Karlheinz Stockhausen, like most other Germans, was now faced with the realities of denazification and the recriminations for an entire country’s crimes. With his mother one of the first murdered by the Nazis for her ‘undesirable’ mental health issues, and his father, a fervent believer of the regime and likely killed in action, Stockhausen was left effectively orphaned. An unwilling participant in mandatory Hitler Youth activities and repulsed by his father’s fanaticism, Stockhausen had already started to distance himself from his father by enrolling in boarding school in 1942, which led to him taking up studies in music teaching. It was only in 1950 that his interest in composition was sparked, almost immediately at the very forefront of avant-garde modernism.

Travelling to Paris in 1952 to undertake study with Olivier Messiaen, Stockhausen met the radical French composer and fellow student of Messiaen, Pierre Boulez. Already having made a name for himself as polemic and unapologetic, Boulez was in the 50’s on the bleeding edge, having proclaimed Schoenberg as the future of music and then, upon his death, immediately dismissing him as a relic of the past in the acrid ‘Schoenberg is Dead’. Boulez would go on to call Stockhausen “the greatest living composer, and the only one I recognise as my peer”, which for the ever-changeable Frenchman was the highest of praise. The two composers, each brimming with creative energy, latched onto the new ideas rapidly filling the post-war vacuum, both finding serialism and then adopting electronics, Stockhausen the earliest with his work in Cologne from 1953, and Boulez in Baden-Baden from 1959.

The two works are both early in each composers’ catalogue, snapshots of this new creative energy post-1945. 12 Notations was written on this cusp, appearing in 1945, a breathless series of miniatures exploring the serialist craze. The number 12 extends beyond the number of movements – each movement is 12 bars long, and with 12 notes in the octave a serial row is made up of 12 sequential notes. Within it too are echoes of the influences in Paris at the time, particularly that of Messiaen and Boulez’s other teacher, René Leibowitz. Boulez’s assessment of his own work is typical acerbic:

“While I did not agree with all that Messiaen was doing, at least he was inventive. And he had his own world. But Leibowitz, [his twelve-tone composition] was just kind of salt on nothing; it was so dry and so unimaginative, only one-to-twelve, twelve-to-one, six-to-one, one-to-seven and so on … it was dreadful. And so I said to myself, well, I can do this too. So I did twelve pieces of twelve bars each, and each piece begins with one, with two, with three, with four and so on. I called that my system, but it doesn’t sound like it. It just didn’t. But the pieces were not fun. They were just spontaneous pieces, because I composed them within two or three days – I don't remember exactly. It was just before Christmas of '45.” —Pierre Boulez, interview with Wolfgang Schaufler, 2010.

Stockhausen’s Klavierstück (‘piano pieces’) are a much more sincere study, a collection that began as a set of four studies in serial techniques and expanded to nineteen over the course of the composer’s lifetime (though 8 of these are derived from his opera cycle Licht [‘Light’, 1977-2003]). Combining a serial tone row with rhythmic proportions derived from the Fibonacci sequence, the work also emphasises Stockhausen’s fascination with the limits of human ability on the reproduction of scored music through his theories of “variable form”. No note will ever be played exactly the same, and the fast repetitions of chords that characterise the work lean on the imperfections that live performance create, letting interest be found in the differences between each repetition and through this anticipating the trends in minimalism of bringing out small details in large homogenous structures.

Far from the jubilant streets of free Paris and the emerging hope and economic miracles of West Germany, Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) was insulated from this energy that sparked a revolution in compositional technique by the impenetrable Iron Curtain. The mind of Dmitri Shostakovich has been the subject of speculation for decades, with grand romantic narratives of embattled composer and secretive dissenter all too easy to read into the bleak darkness that runs through the body of his works.

The revolution of 1917 threw out the monarchy and replaced it with a communist dream that soured into a totalitarian regime of absolute compliance and groupthink. Throughout his life, Shostakovich walked the delicate line between artistic integrity and pleasing the state censors and critics. Frequently, works would be deemed ‘formalist’ by critics and state censors, a nebulous accusation of pretension that ran against the proletariat values and state-mandated style of Socialist Realism his works had to abide by. For every success of Shostakovich’s seemed to come a denouncement, with each apparent transgression against the regime a serious threat to the safety of him and his family. Purges were common, and creatives suspected of harbouring dissident sentiments frequently disappeared into the night.

The 1979 publication of Testimony, the generally discredited memoirs supposedly dictated by the composer to musicologist Solomon Volkov and smuggled out of the Soviet Union, threw fuel on the flame of speculation behind Shostakovich’s true intents behind his works. Western audiences had admired the composer despite the availability of his works being an arm of Soviet cultural propaganda, and already placed the narrative of tortured composer onto the Russian. On visits to the US, they would stand outside his hotel in the US and call for him to jump from his window, making his escape and living free of Soviet artistic constraints. But Shostakovich never jumped, dying in Moscow at the age of 68.

As the second piano trio was composed in 1943-4, Russia faced the terror of the Nazis within its own borders: Shostakovich’s home of Leningrad had been under siege since 1941, and the war effort saw millions of Russians sent to the Eastern Front to face their deaths. Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7, op. 60 Leningrad (1941), was begun in the city before Shostakovich fled further east, and was quickly adopted as a symbol of Russian resilience against the Nazis, being played in the besieged city by remaining musicians, piped over loudspeakers, and across the West.

Not all propaganda was uplifting – both Soviet and Western governments saw the value in broadcasting the war crimes and tragedies of Nazi occupation, and the emerging details of death camps and genocide were publicised to rally further support towards the war effort. The details deeply affected Shostakovich, who also faced the loss of friends and family at the front with the rest of Russia. The second piano trio is explicitly a memorial to mentor and close friend Igor Sollertinsky, but the use of Jewish folk tunes in the final movement have been theorised as an indication that this piece memorialises lives lost in the Holocaust.

The musical material certainly suggests an interpretation tending towards emotional devastation. The haunting cello harmonics of the first movement a ghostly premonition of the intensity to come, building unease towards tense angular lines. A typically ironic movement follows, bombastic in a major key, yet lacking any true sense of triumph through the sharp, biting accents throughout and almost grating repetitions in the strings. The third movement, a passacaglia, opens with eight chords on the piano, compared by Borodin Quartet violinist Rostislav Dubinsky as the hammers of forced labourers in concentration camps, overlaid with weeping strings.

The final movement will sound familiar to those who have heard the composer’s String Quartet No. 8, which quotes this Jewish folk melody among others from across his catalogue in one of the composer’s most striking and well-known works, filled with frantic fury and supposedly penned before a planned suicide. A similar build-up of tension drives this closing movement of the piano trio, as close to a musical cry of anguish as has been composed in the Western catalogue. The movement builds to breaking point, with the melody collapsing to the same ghostly harmonics as the work opened with. Words may not describe the horrors of this period of time, but music may come closer to approximating the most human responses to these unimaginable events. Shostakovich’s second piano trio in Brave New Worlds is a memorial, and a sobering reminder of the events that led to the artistic resurgence post-1945.

BRAVE NEW WORLDS: OUT OF THE RUINS

Thursday 12 September 3pm

Joseph HAYDN Kaiserhymne

Arnold SCHÖENBERG Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte, op. 41

Pierre BOULEZ 12 Notations

Karlheinz STOCKHAUSEN Klavierstück IX

Dimitri SHOSTAKOVICH Piano Trio no. 2 in E minor, op. 67

Paavali Jumppanen (ANAM Artistic Director) director/piano

Philip Lambert narrator

ANAM Musicians

Venue The Good Shepherd Chapel (next to Abbotsford Convent)

Tickets from $20

Bookings anam.com.au or 03 9645 7911

Words by Alex Owens