Words by

Geum Hye Kim

Tourists always flock to Rome. The empires and their outposts have strange allure. Even before the common era, wide-eyed wanderers poured into what they thought to be the economical and political centre of the known world, attracted by the magnificence of the Ancient Roman Empire. In the meantime, thrill-seeking Romans set out to Egypt, which they saw as the glamorous oriental empire.

So, of course, Mendelssohn ended up in Italy in 1830. It was predestined. Mendelssohn made most of his travel, visting Rome, Pompeii, Venice, Naples, and Florence along the way, and he returned to Germany by travelling through Genoa and Milan.

During this time, Mendelssohn worked on his Symphony no. 4 in A major, which is also known as his Italian symphony. Mendelssohn's Fourth Symphony treats its listeners like a tourist. After the aerated, light-filled first movement that sounds giddy with wine, and after the marching-band-like second movement, we are asked to join in the fun of Italian folk dances in the third movement. In other words, the symphony encapsulates Mendelssohn's experience as a leisurely traveller. To cite Peter Laki, “The second-movement Andante con moto was probably inspired by a processional song Mendelssohn heard in Rome. It is occasionally dubbed 'Pilgrim's March,' because of a certain resemblance to the 'Pilgrim's March' from Berlioz's Harold in Italy, another famous 'Italian Symphony' from the 1830s."

Travel destinations are often where friendships are made or broken. It was in Rome in 1831 that Mendelssohn met Berlioz. Some time later, Mendelssohn invited Berlioz to Leipzig, introducing the French composer to the German audience.

It was the Prix de Rome, the French scholarship that allowed young artists to study at the French Academy in Rome, that brought Berlioz to Italy. The Prix de Rome was one of many things that the Napoleons left their footprints in. A few decades before Berlioz won his scholarship, the Napoleons had relocated the Academy to its current location in Vila Medici, and started another Prix de Rome in the Netherlands.

Napoleon, who rose to power during the French Revolution, is from Corsica, an island wedged between Italy and France – and he too could boast a distant relation to the Italian nobility. Music in Italy may not have impressed Berlioz, but the scholarship brought Berlioz close to his heroes: Napoleon Bonaparte, the first and the third. Berlioz produced Te Deum in honour of the first Napoleon, and dedicated his Cantata L’Impériale to Napoleon III, the nephew of Napoleon I, who established his power by turning the first Bonaparte into a political icon. Berlioz would retrace the steps of his heroes whenever the opportunities presented themselves (The Other Worlds of Hector Berlioz by Inge van Rij).

In Berlioz and Mendelssohn's time, Napoleon continued to be admired as both a hero and an antihero - perhaps due to the effect he had on the borders of France, Germany and Italy. Whereas Berlioz admired Napoleon as a heroic man, many Germans saw Napoleon as a tyrant and an invader, and Napoleon's actions contributed to the enmity between France and Germany.

It was also Napoleon who inadvertantly brought the French Revolution to Italy and kickstarted the social movements towards the unification of Italy. Also known as Risorgimento (‘rising again’), the Italian 'revolution' sought to bring Italian states together into an identifiable kingdom – a return to the nationalistic and romanticised ideals of the antiquated Roman Empire. Napoleon III's actions further helped the course of the resurgence.

There’s an ongoing debate about whether Verdi’s music played any role in the course of Risorgimento. Without entering into the debate, what we know for sure is that the social climate of Italy at the time was very much reflected in the composers’ lives and their music, and shaped the Italy that Mendelssohn saw and admired.

By the time the unification of Italy was over, Germany had consolidated itself into a Reich, allowing the proper discussion of the Italian-German relations to begin. At the time, no one had foreseen that the Third Reich would emerge, or that Mussolini and Hitler would eventually form a united front against Russia.

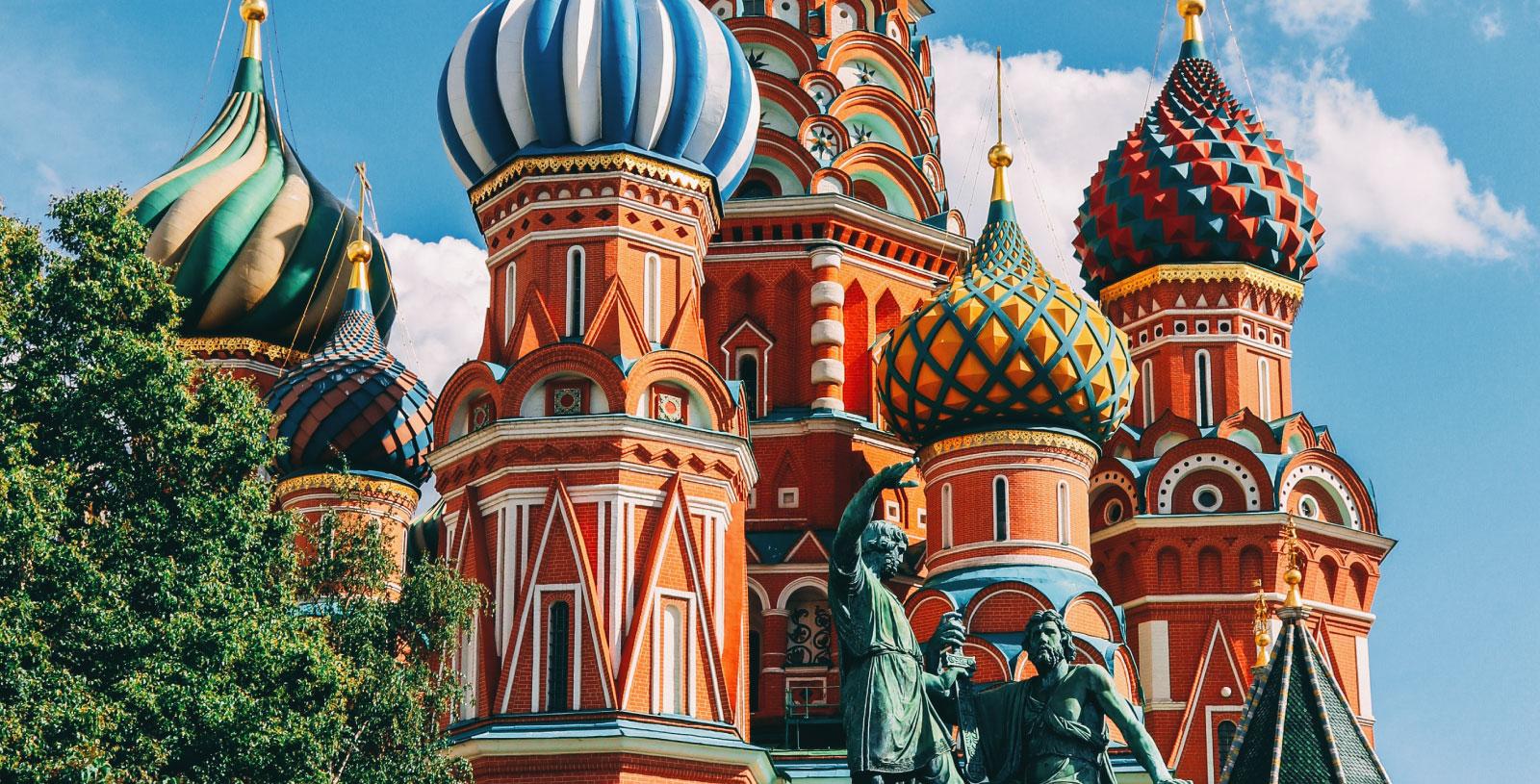

In the 19th century, the House of Romanovs had the god-like sovereignty. As Simon Sebag Montefiore describes in his book, The Romanovs: 1613-1918, “magnificent palaces, elaborate balls, and a culture that produced Pushkin, Tchaikovsky and Tolstoy existed alongside pogroms, torture and murder” under their governance (Washington Post).

We always think of the arts as resisting power, but power produces art, too. The patronage of the nobles, their commissions and the small favours they bestow upon artists dictated the type of genres and art forms that can survive. Romances – also known as Russian art songs – emerged from the parlour and music rooms of the powerful people, and gradually spread out to the rest of the society.

Mikhail Glinka, who is said to have set the tone for the Romances genre, influenced Tchaikovsky’s music greatly. After Glinka, it was Tchaikovsky's music that captured the Romanovs' interest. Konstantin Konstantinovich Romanov – Grand Duke and the poet of the family – even had his poetry set to music written by Tchaikovsky.

Tsar Alexander III was a man who lived knowing his own power, and from whom the first Fabergé egg was created and Tchaikovsky's the Festival Coronation March in D major was written. Alexander III was not a sentimental character, by all accounts. However, Tchaikovsky was one of his favourites. Under the patronage of Alexander, Tchaikovsky received the Order of Saint Vladimir.

“A nation creates music – the composer only arranges it,” Mikhail Glinka insisted. In Russia, the autocracy was the nation – and cast such a long shadow over people's imagination so that the Romanovs still revered these days. Within this cultural context, Tchaikovsky composed Serenade in C major for Strings, combining what’s native to the land with the European influences.

This year, Lucerne Festival’s theme is power. Music is often put on the frontline of the ideological warfare – and the festival explores how the Soviet Union, Germany, Communism, and Patriotism played a modern 'Game of Thrones' using classical music. The festival's program include Mossolows’ Iron Foundry, Sergei Rachmoninov, Alexander Mosolov, Béla Bartók, and, perhaps surprisingly, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Every summer, internationally renowned soloists, chamber musicians, pedagogues, and members of magnificent orchestras come together to form a special ensemble that's known as the Lucerene Festival Orchestra. Gregory Ahss, who has been the Lucerne Festival Orchestra’s concertmaster for a decade, will come to ANAM this August to perform Mendelssohn's Italian Symphony and Tchaikovsky's Serenade in C major for Strings with our musicians.

Gregory Ahss is also Camerata Salzburg's concertmaster – and just a few month ago, Camerata Salzburg performed Tchaikovsky's Serenade for Strings in Madrid. The venue of the performance was Teatro Real, which also enjoyed the patronage of powerful people throughout its history. In 1830, around the time Mendelssohn was abroad in Italy, Teatro Real must have been under construction. Coincidentally, the Theatre reopened in 1997 with a performance of the ballet El sombrero de tres picos ('Three-Cornered Hat'). Our orchestra will also perform selections from this ballet in our season concert Petrushka on 7 September.

What's interesting is that our imagination often associates revolutions with radiating heat – exploding bombs, feverish festivity, and ashes and brimstone. Throughout history, festive activities were offered to the masses as means to control their aggression and provide a small 'theatre' for the common people to work out their frustration. The power, on the other hand, is often imagined to be cold, distant, and fraught with drama. The cultured upper class pulls itself away from the daily hustle and bustle, and takes the role of an observer – often peering down at the ups and downs of life through lorgnette or opera glasses. Does this binary still hold for music that reflects the social and political contexts, or receives direct patronage of the royal rank?

Joy & Heartbreak on Saturday 10 August is the perfect opportunity to hear Mendelssohn's Italian Symphony and Tchaikovsky's Serenade for Strings in one seating. We'd love to know what you think of the performance.

A GATEWAY TO THE SUBLIME

Friday 2 August 11AM

ANAM, South Melbourne Town Hall

FIND OUT MORE

JOY & HEARTBREAK

Saturday 10 August 7.30PM

ANAM, South Melbourne Town Hall

FIND OUT MORE

Israeli violinist Gregory Ahss began his training at the Gnessin School of Music in his native Moscow, continuing studies at the Israeli Conservatory of Music and at the Tel Aviv Music Academy with Lena Mazor and Irina Svetlova. He graduated from the New England Conservatory in Boston where he studied with Donald Weilerstein. While still a student he founded the Tal Piano Trio, which has received numerous awards including first prize at the prestigious Trio di Trieste chamber music competition.

Gregory has appeared as guest director with such notable ensembles as the Mahler chamber orchestra, Orchestra Mozart, Belgrade Philharmonic and the Lucerne Festival Orchestra leading the repertoire ranging from chamber symphonies to full symphonic literature from the violin. Also as a guest leader he appears amongst others with orchestras such as London Symphony, Bavarian Radio Symphony orchestra, Montreal Symphony, Munich Opera, Orchestra della Academia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome and Bamberg Symphony.

He is concertmaster of Camerata Salzburg and the Lucerne Festival Orchestra.

Public domain photos: Hector Berlioz, lithography by August Prinzhofer, 1845; Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, lithography by Friedrich Jentzen, 1837; Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, portrait published by Bain News Service.