O brave new world, that has such people in 't, was Miranda’s hopeful remark to Prospero who didn’t share her daughter’s optimism. Rich in musical references as Shakespeare is, the title for this concert series came from elsewhere - namely, from Aldous Huxley’s similarly named utopian novel. Paradoxically what had inspired Huxley was the Tempest, a play with numerous musical representations, some of which could easily have made it into this concert series.

But as there is no Tempest in this series, neither by Beethoven nor Sibelius, let us begin with Mozart and the revelation of how enlightened a composer he actually was. You see, as a youngster he was trained in proper learned techniques by masters of polyphony, among them the celebrated Italian guru Padre Martini. But in his maturity, he chose to compose music which the masses could grasp and enjoy.

A performance of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis by the New York Philharmonic, conducted by Leonard Bernstein, at the UN headquarters 1955.

The opening concert of this series features the ANAM musicians singing Gregorio Allegri’s famous setting of Psalm 51 (Miserere mei, Deus) followed by a performance of Mozart’s ingeniously melodic wind serenade, the Gran Partita. The story is that 14-year old Wolfgang visited the Vatican and heard the Miserere being performed in the Sistine Chapel, and apparently he wrote down the music from memory.

Mozart’s early acquired compositional virtuosity wasn’t wasted in the popular style he chose to compose in, as his command of voice-leading is omnipresent in his music and something he could never hide, even when he at times attempted to do so in his buffa-style works. With his artful simplicity, Mozart betted on the winning stylistic horse. Soon after his prime, and following the French Revolution, art music was to become even simpler, with Beethoven leading the way for abandoning most baroque techniques for the next couple of decades. Thrown out from the courts, Ancien Régime had no place in music either.

Composer Olivier Messiaen at Stalag VIII-A.

The next concert in the series zooms a century ahead, to witness the collision between high romanticism and emerging trends challenging it. Of particular interest is the appearance of musique concrète, heralded in this program by the Parade; a ballet conceived by a collective consisting of composer Erik Satie, choreographer Leonide Massine, set designer Pablo Picasso, and as the headmaster of the production, the nearly undefinable avant-gardist Jean Cocteau. Cocteau’s mission was to wash away the heaviness of the turn-of-the-century art. He had for instance declared Claude Debussy to be “a mere little Wagner, fallen off a German frying pan”.

Crisis in society can never be hidden, evidence can always be found in art. A powerful case in point is the music of the 1940s, featured in the third concert of this series. We will experience Lord Byron’s ironic condemnation of tyranny in his Ode of Napoleon, in a musical setting by Arnold Schöenberg. In fact, Schöenberg used Byron’s text to take on a contemporary tyrant, Adolf Hitler, who at the time had removed all of his masks and revealed his true, simply evil face.

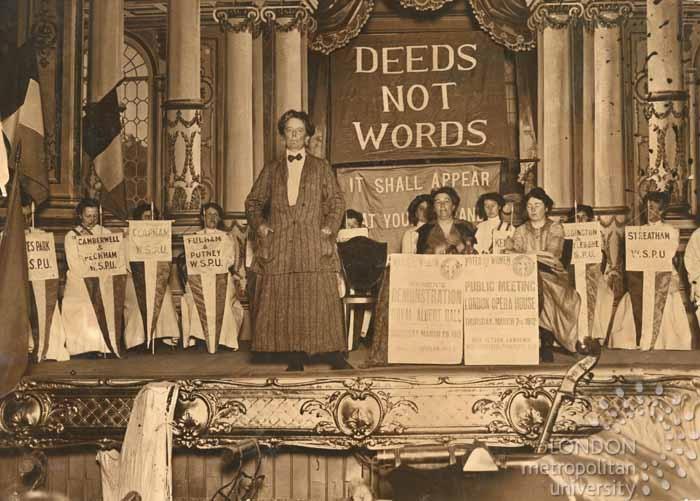

Composer and suffragette Ethel Smyth.

This program also features a much-loved work of the chamber music canon, the Second Piano Trio by Shostakovich. This work reflected the devastation of the war in Soviet Union, in particular the terrible toil of the siege of Leningrad. But the trio is far from patriotic – a significant undercurrent is Shostakovich’s own fate as an artist, on the one hand showcased by Stalin’s regime, but only after having attempted to aesthetically crush him.

Cocteau had wanted to rid art from too much sentiment because he felt it could benefit from it. The generation of composers trying to create music after the catastrophe of World War II were facing a more serious challenge, and felt compelled to altogether step away from the pleasurable nature of the artform. Works by Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez from the late 1940s and early 1950s demonstrate music’s ransformation into a phenomenon which was emotionally numb, but sonically dazzlingly vibrant.

Pauline Oliveros alongside the ♀ Ensemble delivering a performance of "Teach Yourself to Fly" from the "Sonic Meditations" collection, 1970, in Rancho Santa Fe, California.

The final program in this series celebrates activism. William Tell’s legend in the hands of Gioachino Rossini, and Sonic Meditations by Pauline Oliveiros - a communal composition written by an activist - remind us of the societal power warranted to music.

We also wanted to present music that speaks to today’s world. To accomplish this, we have asked the ANAM musicians to choose works for the final concert that represent the current time and themes that their generation feels are commanding to be listened to.

Miranda’s optimism, Prospero’s skepticism, Huxley’s daunting vision; take your pick, music says it all! Throughout the ages, human thought and social action have provided inspiration for composers. They have taken on the task of recording the zeitgeist in their music. Our task may simply be to enjoy that music, but the experience will be greatly enriched once we discover the meanings and motivations embedded in it.

Words by Paavali Jumppanen

First published in volume 50 of Music Makers.

BRAVE NEW WORLDS

Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité: Mozart and the sound of the enlightenment Wednesday 27 March 2024, 3pm

Fin de Siècle and Modernism Thursday 20 June, 3pm

Out of the Ruins Thursday 12 Septembe, 3pm

Activism Thursday 24 October, 3pm

The Good Shepherd Chapel, Abbotsford

FIND OUT MORE